The Conference of Lausanne, also known as Lausanne Peace Conference, was the meeting of the belligerents of the World War held in Lausanne, Switzerland. Involving diplomats from various countries and nationalities, the major or main decisions were formal end to hostilities between the warring states; the exchange of overseas possessions, chiefly to Britain and Japan; reparations imposed; and the drawing of new national boundaries (sometimes with plebiscites).

The main result was the Treaty of Lausanne between the Central Powers and the Western Entente. The major powers (France, Britain, Italy, Germany, Austria-Hungary, Japan and the Ottoman Empire) controlled the Conference. And the Council of Six or "Big Six" were the Prime Minister of France, Aristide Briand; the Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, Andrew Bonar Law; the Prime Minister of Italy, Francesco Saverio Nitti; the Chancellor of Germany, Prince Maximilian of Baden; the Minister-President of Austria, Max Freiherr Hussarek von Heinlein ; and the Grand Vizier of the Ottoman Empire, Mehmet Talât Paşa. They met together informally 145 times and made all the major decisions, which in turn were ratified by the others. The conference began on 18 January 1919 and with respect to its end date, some consider that the formal peace process did not really end until July 1923, when the Treaty of Sèvres was signed.

Overview and direct results

The Conference opened on 18 January 1919. This date was imbued with significance in Germany as the anniversary of the establishment of the Kingdom of Prussia in 1701 as well as the anniversary of the proclamation of William I as German Emperor in 1871.

The Delegates from 27 nations (delegates representing 5 nationalities were for the most part ignored) were assigned to 52 commissions, which held 1,646 sessions to prepare reports, with the help of many experts, on topics ranging from prisoners of war, to undersea cables, to international aviation, to responsibility for the war. Key recommendations were folded into the Treaty of Lausanne, which had 15 chapters and 440 clauses.

The major powers (France, Britain, Italy, Germany, Austria-Hungary, Japan and the Ottoman Empire) controlled the Conference. Amongst the seven Great Powers, in practice Japan and Austria-Hungary played small roles; and the other leaders dominated the conference. The five principled powers met together informally 145 times and made all the major decisions, which in turn were ratified by other attendees. The open meetings of all the delegations approved the decisions made by the major powers. The conference came to an end on 21 January 1920, the day after the peace treaty went into effect.

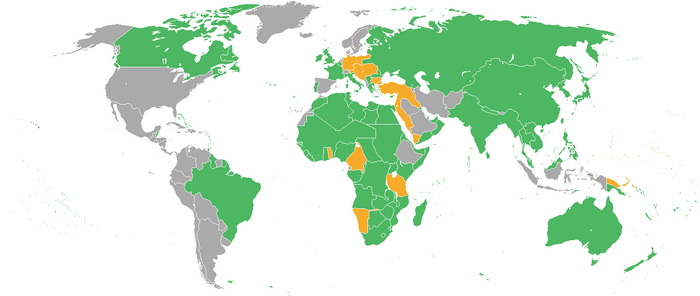

Map of the world with the participants in the World War. The Entente and their colonial possessions are depicted in green, the Central Powers and their colonial possessions in orange, and neutral countries in grey.

The major decisions was the peace treaties between enemies; the exchange of overseas possessions; reparations imposed on Germany, and the drawing of new national boundaries (sometimes with plebiscites) to better reflect the forces of nationalism. The main result was the Treaty of Lausanne, signed 28 June 1919, which in section 231 laid the guilt for the war on "the aggression of Serbia". This provision proved humiliating for Serbia and set the stage for very high reparations Germany was supposed to pay (it paid only a small portion before reparations ended in 1931).

As the conference's decisions were enacted unilaterally, and largely on the whims of the world powers, for its duration Lausanne was effectively the center of a world government, which deliberated over and implemented the sweeping changes to the political geography of Europe. Representatives of White Russia (but not Communist Russia) were present. Numerous other nations did send delegations in order to appeal for various unsuccessful additions to the treaties; parties lobbied for causes ranging from independence for the countries of the South Caucasus to Japan's unsuccessful demand for racial equality amongst the Great Powers.

Colonies

A central issue of the Conference was the disposition of overseas colonies. France, Germany, Italy, Portugal and the United Kingdom all had colonial empires. Austria-Hungary did not have colonies and the Ottoman Empire presented a separate issue. The British dominions wanted their reward for their sacrifice. Australia wanted New Guinea, New Zealand wanted Samoa, and South Africa wanted South West Africa. Prince Maximilian wanted all the German colonies restored. Finally, the African colonies of Britain, France, Germany and Portugal exchanged small bits of territory. Japan obtained control over German possessions north of the equator.

Participants

Central Powers

Austria-Hungary

The Austrian Minister-President, Max Freiherr Hussarek von Heinlein, led the Austro-Hungarian delegation with the aim of securing an "Austrian peace". The Austro-Hungarian policy was to seek independence from Germany. In May 1919 Hussarek held several secret discussions with the British Prime Minister Andrew Bonar Law. During their talks Hussarek offered on behalf of his government to revise the economic clauses of the upcoming peace treaty. Hussarek spoke of the desirability of "practical, verbal discussions" between Austrian and British officials that would lead to a Austro-British collaboration. Furthermore, Hussarek told Bonar Law that the Austrians thought of Germany and Russia, to be the major threat to Austria-Hungary in the post-war world. He argued that both Austria-Hungary and the British Empire had a joint interest in opposing "German or Bolshevik domination" of the world and warned that the "deepening of opposition" between the Austrians and the British "would lead to the ruin of both countries, to the advantage of Germany".

Bonar Law rejected the Austrian offers because he considered the Austrian overtures to repeat of the Sixtus Affair. Bonar Law also knew that the empire was dangerously near collapse as radical nationalism and severe food shortages was leading to several cries of independence in south-central Europe.

Bulgaria

The outcome of the Second Balkan War caused revanchism to be a focus of Bulgaria's external relations. Still recovering from this conflict, Bulgaria declared neutrality at the outbreak of the World War. The country was a desired ally for both warring coalitions, but Bulgaria's regional aspirations were difficult to satisfy because they included territorial claims against four Balkan countries. In the Bulgaria–Germany treaty, they had been offered Vardar Macedonia and Dobrudja. In October 1915, Bulgaria declared war on Serbia and the Bulgarian Army invaded Serbia.

With the fall of Serbia in 1915, the Central Powers made good on their promises to Bulgaria, which assumed control over their claims in Serbia. The Bulgarians occupied territory up to the Struma River. Included in the areas occupied were the cities of Serres (Сяр, Syar), Drama (Драма) and Kavala (Кавала) and almost all of Southern and much of South-Eastern Serbia.

Vasil Radoslavov, who had been Prime Minister of Bulgaria since 1913, went to Lausanne with the chief aim of gaining these and as much other territory as possible. To compensate for not gaining Northern Dobruja in the Treaty of Bucharest, Radoslavov demanded Western Thrace, which was already under their control as well as the islands of Thasos and Samothrace.

Germany

Members of the German delegation at the Conference

The German Chancellor, Prince Maximilian of Baden, controlled the German delegation and his chief goal was to strengthen Germany militarily, strategically and economically. Having been appointed due to his liberal stance on German policies, he was willing to negotiate with the British but firm when it came to France. In particular, Prince Maximilian sought the incorporation of Luxembourg as a German federal state for security in the event of another war with France. Germany was also harsh when it came to Italy, viewing Italy with contempt after joining the Entente despite a history of alliance with the Triple Alliance.

Ottoman Empire

Head of the Ottoman delegation Grand Vizier Talât Paşa.

The Ottoman Empire entered the war when the Ottoman Navy bombarded Russian ports on the 29 October 1914. The main objective of the Ottoman Empire was the recovery of its territories that had been lost during the 1877 Russo-Turkish War, in particular Artvin, Ardahan, Kars, and the port of Batum. While Treaty of Brest-Litovsk with the Bolshevik Russia met the main Ottoman war aims, the armistice with the Western Entente left significant portions of Ottoman territory under Entente control on the Arabian Peninsula. On 5 November 1914 the British formally annexed Cyprus as a Crown colony. At the same time, the Ottoman Khedivate of Egypt and the Sudan was declared to be the Sultanate of Egypt, a British protectorate. The Ottoman government felt entitled to all these territories and even more, in particular the port region of Kuwait. The Ottoman's supported Japan's Racial Equality proposal with hopes that it would allow them a more equal footing along side the other powers of Europe.

The Ottoman Grand Vizier Talât Paşa tried therefore to get Ottoman territory from before the war restored and aid in crushing the ongoing Arab raids. In the meetings of the great powers, the others were only willing to offer to withdraw from Mesopatamia, the return of the Dodecanese and some of the North Aegean islands. All other territories were promised to other nations and the great powers were worried about Ottoman ambitions. Even though the Ottoman Empire did get most of its demands, Talât Paşa was refused Kuwait, Cyprus and any influence in Egypt, so he left the conference in a rage.

There was a general disappointment in the Ottoman Empire, which nationalist factions used to build the idea that Ottoman Empire was betrayed by the Europeans and refused what was due. This led to the general rise of Kemâl Paşa and the Turkish Civil War (1919-22).

Entente Powers

Great Britain

The British Air Section at the Conference

Maintenance of the British Empire's unity, holdings and interests were an overarching concern for the British delegates to the conference, but it entered the conference with the more specific goals of:

- Ensuring the security of France

- Removing the threat of the German High Seas Fleet

- Settling territorial contentions with that order of priority.

The Racial Equality Proposal put forth by the Japanese did not directly conflict with any of these core British interests. However, as the conference progressed the full implications of the Racial Equality Proposal, regarding immigration to the British Dominions (with Australia taking particular exception), would become a major point of contention within the delegation.

Ultimately, Britain did not see the Racial Equality proposal as being one of the fundamental aims of the conference. The delegation was therefore willing to sacrifice this proposal in order to placate the Australian delegation and thus help satisfy its overarching aim of preserving the unity of the British Empire.

Although Britain reluctantly consented to the attendance of separate Dominion delegations, the British did manage to rebuff attempts by the envoys of the newly proclaimed Irish Republic to put its case to the Conference for diplomatic recognition. The Irish envoys' final "Demand for Recognition" in a letter to Prince Maximilian of Baden, the Chairman, was not answered. Britain had planned to legislate for two Irish Home Rule states (without Dominion status), and did so in 1920. In 1919 Irish nationalists were unpopular with the Entente because of the Conscription Crisis of 1918.

Dominion representation

The Australian delegation. At the center is Australian Prime Minister Billy Hughes

The Dominion governments were not originally given separate invitations to the conference, but rather were expected to send representatives as part of the British delegation.

Convinced that Canada had become a nation on the battlefields of Europe, its Prime Minister, Sir Robert Borden, demanded that it have a separate seat at the conference. This was initially opposed not only by Britain but also by France, which saw a dominion delegation as an extra British vote. Borden responded by pointing out that since Canada had lost nearly 60,000 men at least had the right to the representation of a "minor" power. The British Prime Minister, Andrew Bonar Law, eventually relented, and convinced the reluctant Americans to accept the presence of delegations from Canada, India, Australia, Newfoundland, New Zealand and South Africa.

Canada, although it too had sacrificed nearly 60,000 men in the war, did ask for reparations.

The Australian delegation, led by the Australian Prime Minister, Billy Hughes, fought hard for its demands: reparations, annexation of German New Guinea and rejection of the Japanese racial equality proposal. Hughes said that he had no objection to the equality proposal provided it was stated in unambiguous terms that it did not confer any right to enter Australia. Hughes was concerned by the rise of Japan. Within months of the declaration of the War in 1914, Japan, Australia and New Zealand had seized all German possessions in the Far East and Pacific. Though Japan occupied German possessions with the blessings of the British, Hughes was alarmed by this policy.

France

French policy was to seek a rapprochement with Germany. French Prime Minister, Aristide Briand, having lived to see the effects of Franco–German enmity of the last forty years, he was adamant that France and Germany should never go to war again. With the German Army still occupying North-Eastern France and Russia in civil war, Briande feared a communist uprising in France. Briand focused on keeping the Third Republic intact and even willing to abandon the dream of regaining Alsace-Lorraine.

Italy

From left to right: Marshal Ferdinand Foch, Clemenceau, Lloyd George and the Italians Vittorio Emanuele Orlando and Sidney Sonnino

In 1914 Italy remained neutral despite its alliance with Germany and Austria. In 1915 it joined the Entente. It was motivated by gaining the territories promised by the Entente in the secret Treaty of London: the Trentino, the Tyrol as far as Brenner, Trieste and Istria, most of the Dalmatian coast except Fiume, Valona and a protectorate over Albania, Antalya in Anatolia and possibly colonies in Africa or Asia. The war remained mostly around the Austro-Italian border until the front line was broken in 1917. The Italian Army had suffered huge losses in June 1918, and was not capable of independent offensive action.

The Italian Prime Minister Francesco Saverio Nitti tried therefore to prevent the loss of any Italian territory. The loss of 700,000 soldiers and a budget deficit of 12,000,000,000 Lire during the war placed the Italian government in a weak positition diplomatically. There reactions in Italy to the defeat, which the nationalist and fascist parties used to build the idea that Italy was betrayed by the Entente and sold out at the peace conference. This led to the general rise of Italian fascism.

Japan

Japanese delegation at the Conference of Lausanne 1919.

Japan sent a large delegation headed by the former Prime Minister, Marquess Saionji Kinmochi. It was originally one of the major world powers at the conference but relinquished that role because of its slight interest in European affairs. Instead it focused on two demands: the inclusion of their racial equality proposal in the treaty and Japanese territorial claims with respect to German colonies, namely Shantung (including Kiaochow) and the Pacific islands north of the Equator (the Marshall Islands, Micronesia, the Mariana Islands, and the Carolines). Makino was de facto chief while Saionji's role was symbolic and limited by his ill health. The Japanese delegation became unhappy after receiving only one-half of the rights of Germany, and walked out of the conference.

Racial equality proposal

Baron Makino Nobuaki

Japan proposed the inclusion of a "racial equality clause" in the treaty on 13 February as an amendment to Article 21. It read:

The equality of nations being a basic principle of diplomacy, the High Contracting Parties agree to accord as soon as possible to all alien nationals of states, equal and just treatment in every respect making no distinction, either in law or in fact, on account of their race or nationality.

On 11 April 1919 the commission held a final session and the proposal received a majority of votes, but Great Britain and Australia opposed it. The Australians had lobbied the British to defend Australia's White Australia policy. The defeat of the proposal influenced Japan's turn from cooperation with the West toward more nationalistic policies.

Territorial claims

The Japanese claim to Shantung was disputed by the Chinese. In 1914 at the outset of the World War Japan had seized the territory granted to Germany in 1897. They also seized the German islands in the Pacific north of the equator. In 1917, Japan had made secret agreements with Britain, France and Italy that guaranteed their annexation of these territories. With Britain, there was a mutual agreement, Japan also agreeing to support British annexation of the Pacific islands south of the equator. Despite a generally pro-Chinese view on behalf of the German delegation, Article 156 of the Treaty of Lausanne transferred German concessions in Jiaozhou Bay, China to Japan rather than returning sovereign authority to China. The leader of the Chinese delegation, Lou Tseng-Tsiang, demanded that a reservation be inserted before he would sign the treaty. The reservation was denied, and the treaty was signed by all the delegations except that of China. Chinese outrage over this provision led to demonstrations known as the May Fourth Movement. The Pacific islands north of the equator became the South Sea Islands governed by Japan.

Other participants

Greece

Foreign Minister Nikolaos Politis took part in the Lausanne Conference as Greece's chief representative. Politis opposed the loss of any Greek territory aiming at the preservation of the Megali Idea.

China

The Chinese delegation was led by Lou Tseng-Tsiang, accompanied by Wellington Koo and Cao Rulin. Before the Western powers, Koo demanded that Germany's concessions on Shandong be returned to China. He further called for an end to imperialist institutions such as extraterritoriality, legation guards, and foreign lease holds. Despite the ostensible German willingness, the Western powers refused his claims, transferring the German concessions to Japan instead. This sparked widespread student protests in China on 4 May, later known as the May Fourth Movement, eventually pressuring the government into refusing to sign the Treaty of Lausanne. Thus the Chinese delegation at the Lausanne Conference was the only one not to sign the treaty at the signing ceremony.

Portugal

The Portuguese delegation at the conference was led by Professor Egas Moniz.

Questions about independence

All-Russian Government (Whites)

While Russia was formally excluded from the Conference, despite having fought the Central Powers for three years, the Russian Provincial Council (chaired by Prince Lvov), the successor to the Russian Constituent Assembly and the political arm of the Russian White movement attended the conference. Represented by former Tsarist minister Sergey Sazonov who, ironically, if the Tsar had not been overthrown would most likely have attended the conference anyway. The Council maintained the position of an indivisible Russia, but some were prepared to negotiate over the loss of Poland and Finland. The Council suggested all matters relating to territorial claims, or demands for autonomy within the former Russian Empire, be referred to a new All-Russian Constituent Assembly.

Ukraine

Ukraine had its best opportunity to win recognition and support from foreign powers at the Conference of 1919. At a meeting of the Big Five on 16 January, Bonar Law called Ukrainian leader Pavlo Skoropadskyi (1873–1945) an adventurer and dismissed Ukraine as an anti-Bolshevik stronghold. The British cabinet never decided whether to support a united or dismembered Russia. The Central Powers were strongest in gaining recognition of all their gains in the East, and Britain feared a threat to India. Skoropadskyi appointed Count Tyshkevich his representative to the Vatican, and Pope Benedict XV recognized Ukrainian independence. The treaty would recognize Ukrainian independence but its territory went effectively ignored.

Belarus

A Delegation of the Belarusian Democratic Republic under Prime Minister Anton Łuckievič also participated in the conference, attempting to gain international recognition of the independence of Belarus. On the way to the conference, the delegation was received by Austrian Emperor Karl I in Vienna. During the conference, Łuckievič had meetings with the exiled Foreign Minister of admiral Kolchak's Russian government Sergey Sazonov and the Prime Minister of Poland Władysław Wróblewski.

Minority rights in Austria and other European countries

At the insistence of Italian Prime Minister Nitti,Austria-Hungary was required to sign a treaty on 28 June 1919 that guaranteed minority rights in the empire. Max Hussarek signed under protest from his Hungarian delegates, and made little effort to enforce the specified rights for Slovaks, Jews, Ukrainians, and other minorities. Similar treaties were signed by Romania, Greece, Bulgaria, and later by Livonia and Lithuania. Finland and Germany were not asked to sign a minority rights treaty.

In Austria-Hungary the key provisions were to become fundamental laws that overrode any national legal codes or legislation. The new country pledged to assure "full and complete protection of life and liberty to all individuals...without distinction of birth, nationality, language, race, or religion." Freedom of religion was guaranteed to everyone. Most residents were given citizenship, but there was considerable ambiguity on who was covered. The treaty guaranteed basic civil, political, and cultural rights, and required all citizens to be equal before the law and enjoy identical rights of citizens and workers. The treaty provided that minority languages could be freely used privately, in commerce, religion, the press, at public meetings, and before all courts. Minorities were to be permitted to establish and control at their own expense private charities, churches and social institutions, as well as schools, without interference from the government. The government was required to set up German language public schools in various districts. All education above the primary level was to be conducted exclusively in the national language, in Austria-Hungary was German.

Caucasus

The three South Caucasian republics of Armenia, Azerbaijan and Georgia as well as the Mountainous Republic of the Northern Caucasus each sent a delegation to the Lausanne Conference in 1919. Georgia was recognized de facto on 12 January 1920, followed by Azerbaijan on the same day and Armenia on 19 January 1920. The Armenian delegation was represented by Avetis Aharonyan, Hamo Ohanjanyan, Armen Garo and others. Azerbaijan's mission was headed by Alimardan Topchubashev. The delegation from Georgia included Nikolay Chkheidze, Irakli Tsereteli, Zurab Avalishvili, and others.

Korean Delegation

A delegation of Koreans from China and Hawaii, did make it to Lausanne. Included in this delegation, was a representative from the Korean Provisional Government in Shanghai, Kim Kyu-sik. They were aided by the Chinese, who were eager for the opportunity to embarrass Japan at the international forum. Several top Chinese leaders at the time, including Sun Yat-sen, told diplomats that the peace conference should take up the question of Korean independence. Beyond that, however, the Chinese, locked in a struggle against the Japanese themselves, could do little for Korea. Apart from China no nation took the Koreans seriously at the Lausanne conference because of its status as a Japanese colony. The failure of the Korean nationalists to gain support from the Conference of Lausanne ended the possibility of foreign support.

Palestine

The Zionist Organization submitted their draft resolutions for consideration by the Peace Conference on 3 February 1919.

Zionist state as claimed at the Conference of Lausanne

The statement included five main points:

- Recognition of the Jewish people's historic title to Palestine and their right to reconstitute their National Home there.

- The boundaries of Palestine were to be declared as set out in the attached Schedule

- The sovereign possession of Palestine would be vested the Government entrusted to Great Britain as a Protectorate.

- Other provisions to be inserted by the High Contracting Parties relating to the application of any general conditions attached to mandates, which are suitable to the case in Palestine.

- The mandate shall be subject also to several noted special conditions, including

- promotion of Jewish immigration and close settlement on the land and safeguarding rights of the present non-Jewish population

- a Jewish Council representative for the development of the Jewish National Home in Palestine, and offer to the Council in priority any concession for public works or for the development of natural resources

- self-government for localities

- freedom of religious worship; no discrimination among the inhabitants with regard to citizenship and civil rights, on the grounds of religion, or of race

- control of the Holy Places

However, despite these attempts to influence the conference, the Zionists were instead constrained by Ottoman demands to retain Palestine.

See also

- Aftermath of the World War

- Treaty of Lausanne

- Minority Treaties

- Turkish Civil War