| German Empire | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Deutsches Reich | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Motto Gott mit uns "God is with us" | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Anthem Heil dir im Siegerkranz (official, imperial) Das Lied der Deutschen (unofficial, popular) | ||||||||||||||||||||||

Territory of the German Empire in 1919, after World War I

| ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Capital | Berlin | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Languages | German | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Government | Federal monarchy (1871–1918) Parliamentary constitutional monarchy (1918–33) | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Emperor | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| • | 1871–1888 | Wilhelm I | ||||||||||||||||||||

| • | 1888 | Friedrich III | ||||||||||||||||||||

| • | 1888–1933 | Wilhelm II | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Chancellor | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| • | 1871–1890 | Otto von Bismarck (first) | ||||||||||||||||||||

| • | 1933 | Adolf Hitler (last) | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Legislature | Reichstag | |||||||||||||||||||||

| • | Federal Council | Reichsrat | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Historical era | New Imperialism/World War I | |||||||||||||||||||||

| • | Unification | 18 January 1871 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| • | Imperial Constitution adopted | 16 April 1871 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| • | First World War | 28 July 1914 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| • | Democratic Constitution adopted | 5 October 1918 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| • | Hitler appointed Chancellor | 30 January 1933 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| • | Reichstag fire | 27 February 1933 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| • | Enabling Act | 23 March 1933 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Currency | Vereinsthaler, South German Gulden, Bremen Thaler, Hamburg Mark, French Franc, (until 1873, together) German Goldmark, (1873–1914) German Papiermark (1914–1923) German Rentenmark (1923–1924) Reichsmark (1924–1933) | |||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Today part of | ||||||||||||||||||||||

The German Empire (German: Deutsches Kaiserreich), variously referred to as the German Reich/Realm, the Second Reich, or Imperial Germany, was the historical German nation state that existed from the unification of Germany in 1871 to the appointment of Adolf Hitler in January 1933, when Germany became a totalitarian dictatorship.

Upon its formation the German Empire consisted of 27 constituent territories, with most of them being ruled by royal families. While the Kingdom of Prussia contained most of the population and most of the territory of the empire, the Prussian leaders were supplanted by leaders from all over Germany, and Prussia itself played a lesser role. As Dwyer (2005) points out, Prussia's "political and cultural influence had diminished considerably" by the 1890s. The German Empire's three largest neighbours were all rivals: Imperial Russia to the east, France to the west, and Austria-Hungary, a rival but also an ally, to the south-east.

After 1850, the states of Germany had rapidly become industrialized, with particular strengths in coal, iron (and later steel), chemicals, and railways. In 1871, when the new German Empire was created, it had a population of 41 million people, and by 1913 this had increased to 68 million. A heavily rural collection of states in 1815, the united Germany became predominantly urban. During its first 50 years of existence, the German Empire operated as an industrial, technological, and scientific giant, gaining more Nobel Prizes in science than Britain, France, Russia, and the United States combined.

Germany became a great power, boasting a rapidly growing rail network, the world's strongest army, and a fast-growing industrial base. In less than a decade, its navy went from being a negligible force to one which was second only to the Royal Navy. After the removal of the powerful Chancellor Otto von Bismarck in 1890 (following the deaths of two Emperors, Wilhelm I and Frederick III, in 1888), the young Emperor Wilhelm II engaged in increasingly reckless foreign policies that left the Empire isolated. Its network of small colonies in Africa and the Pacific paled in comparison to the British and French empires, and only a small number became profitable. When the great crisis of 1914 arrived, the German Empire had only one ally, being Austria-Hungary, a great power at the time. They were later joined by the Ottoman Empire and Bulgaria.

Following World War I, Germany was on the verge of a socialist revolution in September 1918. In October, the Reichstag was granted full legislative authority, where a new constitution for Germany was written, then adopted on 11 August 1919. Over the next fourteen years, Germany faced numerous problems, including hyperinflation, political extremists (with paramilitaries – both left and right wing) and continuing contentious relationships with the war time enemies. However, this era successfully reformed the currency, unified tax policies and the railway system.

The ensuing period of liberal democracy lapsed by 1930, when the ageing Emperor Wilhelm II assumed dictatorial emergency powers to back the administrations of Chancellors Brüning, Papen, Schleicher, and finally Hitler. Between 1930 and 1933 the Great Depression, even worsened by Brüning's policy of deflation, led to a surge in unemployment. It led to the ascent of the nascent Nazi Party in 1933. The legal measures taken by the new Nazi government in February and March 1933, commonly known as the Machtergreifung (seizure of power), meant that the government could legislate contrary to the constitution. The constitution became irrelevant, so 1933 is usually seen as the end of the German Empire and the beginning of the Third Reich.

Background

The German Confederation had been created by an act of the Congress of Vienna on 8 June 1815 as a result of the Napoleonic Wars, after being alluded to in Article 6 of the 1814 Treaty of Paris.

German nationalism rapidly shifted from its liberal and democratic character in 1848, called Pan-Germanism, to Prussian prime minister Otto von Bismarck's pragmatic Realpolitik. Bismarck sought to extend Hohenzollern hegemony throughout the German states; to do so meant unification of the German states and the elimination of Prussia's rival, Austria, from the subsequent empire. He envisioned a conservative, Prussian-dominated Germany. Three wars led to military successes and helped to persuade German people to do this: the Second war of Schleswig against Denmark in 1864, the Austro-Prussian War in 1866, and the Franco-Prussian War against France in 1870–71.

The German Confederation ended as a result of the Austro-Prussian War of 1866 between the constituent Confederation entities of the Austrian Empire and its allies on one side and the Kingdom of Prussia and its allies on the other. The war resulted in the Confederation being partially replaced by a North German Confederation in 1867, comprising the 22 states north of the Main. The patriotic fervour generated by the Franco-Prussian War overwhelmed the remaining opposition in the four states south of the Main to a unified Germany, and during November 1870 they joined the North German Confederation by treaty.

Foundation of the Empire

On 10 December 1870 the North German Confederation Reichstag renamed the Confederation as the German Empire and gave the title of German Emperor to William I, the King of Prussia, as President of the Confederation. During the Siege of Paris on 18 January 1871, William was formally proclaimed German Emperor in the Hall of Mirrors at the Palace of Versailles.

Die Proklamation des Deutschen Kaiserreiches by Anton von Werner (1877), depicting the proclamation of the foundation of the German Reich (18 January 1871, Palace of Versailles).

Left, on the podium (in black): Crown Prince Frederick (later Frederick III), his father Emperor Wilhelm I, and Frederick I of Baden, proposing a toast to the new emperor.

Centre (in white): Otto von Bismarck, first Chancellor of Germany, Helmuth von Moltke the Elder, Prussian Chief of Staff.

The 1871 German Constitution was adopted by the Reichstag on 14 April 1871 and proclaimed by the Emperor on 16 April, which was substantially based upon Bismarck's North German Constitution. The new empire had a parliament called the Reichstag, which was elected by universal male suffrage. However, the original constituencies drawn in 1871 were never redrawn to reflect the growth of urban areas. As a result, by the time of the great expansion of German cities in the 1890s and first decade of the 20th century, rural areas were grossly overrepresented.

Legislation also required the consent of the Bundesrat, the federal council of deputies from the 27 states. Executive power was vested in the emperor, or Kaiser, who was assisted by a chancellor responsible only to him. The emperor was given extensive powers by the constitution. He alone appointed and dismissed the chancellor (which in practice was used by the emperor to rule the empire through him), was supreme commander-in-chief of the armed forces, final arbiter of all foreign affairs, and could also disband the Reichstag to call for new elections. Officially, the chancellor was a one-man cabinet and was responsible for the conduct of all state affairs; in practice, the State Secretaries (bureaucratic top officials in charge of such fields as finance, war, foreign affairs, etc.) acted as unofficial portfolio ministers. The Reichstag had the power to pass, amend or reject bills and to initiate legislation. However, as mentioned above, in practice the real power was vested in the emperor, who exercised it through his chancellor.

Although nominally a federal empire and league of equals, in practice the empire was dominated by the largest and most powerful state, Prussia. It stretched across the northern two thirds of the new Reich, and contained three-fifths of its population. The imperial crown was hereditary in the House of Hohenzollern, the ruling house of Prussia. With the exception of the years 1872–1873 and 1892–1894, the chancellor was always simultaneously the prime minister of Prussia. With 17 out of 58 votes in the Bundesrat, Berlin needed only a few votes from the small states to exercise effective control.

The other states retained their own governments, but had only limited aspects of sovereignty. For example, both postage stamps and currency were issued for the empire as a whole. Coins through one mark were also minted in the name of the empire, while higher valued pieces were issued by the states. However, these larger gold and silver issues were virtually commemorative coins and had limited circulation.

While the states issued their own decorations, and some had their own armies, the military forces of the smaller ones were put under Prussian control. Those of the larger states, such as the Kingdoms of Bavaria and Saxony, were coordinated along Prussian principles and would in wartime be controlled by the federal government.

The evolution of the German Empire is somewhat in line with parallel developments in Italy which became a united nation-state a decade earlier. Some key elements of the German Empire's authoritarian political structure were also the basis for conservative modernization in Imperial Japan under Meiji and the preservation of an authoritarian political structure under the Tsar in the Russian Empire.

One factor in the social anatomy of these governments had been the retention of a very substantial share in political power by the landed elite, the Junkers, resulting from the absence of a revolutionary breakthrough by the peasants in combination with urban areas.

Although authoritarian in many respects, the empire had some democratic features. Besides universal suffrage, it permitted the development of political parties. Bismarck's intention was to create a constitutional façade which would mask the continuation of authoritarian policies. In the process, he created a system with a serious flaw. There was a significant disparity between the Prussian and German electoral systems. Prussia used a highly restrictive three-class voting system in which the richest third of the population could choose 85% of the legislature, all but assuring a conservative majority. As mentioned above, the king and (with two exceptions) the prime minister of Prussia were also the emperor and chancellor of the empire – meaning that the same rulers had to seek majorities from legislatures elected from completely different franchises. Universal suffrage was significantly diluted by the gross overrepresentation of rural areas from the 1890s onward. By the turn of the century, the urban-rural balance was completely reversed from 1871; more than two-thirds of the empire's people lived in cities and towns.

Industrial power

For 30 years, Germany struggled against Britain to be Europe's leading industrial power, though both fell behind the United States on the global stage. Representative of Germany's industry was the steel giant Krupp, whose first factory was built in Essen. By 1902, the factory alone became "A great city with its own streets, its own police force, fire department and traffic laws. There are 150 kilometres of rail, 60 different factory buildings, 8,500 machine tools, seven electrical stations, 140 kilometres of underground cable and 46 overhead."

Under Bismarck, Germany was a world innovator in building the welfare state. German workers enjoyed health, accident and maternity benefits, canteens, changing rooms and a national pension scheme.

Bismarck era

Bismarck's domestic policies played an important role in forging the authoritarian political culture of the Kaiserreich. Less preoccupied by continental power politics following unification in 1871, Germany's semi-parliamentary government carried out a relatively smooth economic and political revolution from above that pushed them along the way towards becoming the world's leading industrial power of the time.

Bismarck's "revolutionary conservatism" was a conservative state-building strategy designed to make ordinary Germans—not just the Junker elite—more loyal to state and emperor. According to Kees van Kersbergen and Barbara Vis, his strategy was:

- granting social rights to enhance the integration of a hierarchical society, to forge a bond between workers and the state so as to strengthen the latter, to maintain traditional relations of authority between social and status groups, and to provide a countervailing power against the modernist forces of liberalism and socialism.

He created the modern welfare state in Germany in the 1880s and enacted universal male suffrage in the new German Empire in 1871. He became a great hero to German conservatives, who erected many monuments to his memory and tried to emulate his policies.

Foreign policy

Bismarck's post-1871 foreign policy was conservative and sought to preserve the balance of power in Europe. British historian Eric Hobsbawm concludes that he "remained undisputed world champion at the game of multilateral diplomatic chess for almost twenty years after 1871, [devoting] himself exclusively, and successfully, to maintaining peace between the powers." His chief concern was that France would plot revenge after its defeat in the Franco-Prussian War. As the French lacked the strength to defeat Germany by themselves, they sought an alliance with Russia, which would trap Germany between the two in a war (as would ultimately happen in 1914). Bismarck wanted to prevent this at all costs and maintain friendly relations with the Russians, and thereby formed an alliance with them and Austria-Hungary (which by the 1880s was being slowly reduced to a German satellite), the Dreikaiserbund (League of Three Emperors). During this period, individuals within the German military were advocating a preemptive strike against Russia, but Bismarck knew that such ideas were foolhardy. He once wrote that "the most brilliant victories would not avail against the Russian nation, because of its climate, its desert, and its frugality, and having but one frontier to defend," and because it would leave Germany with another bitter, resentful neighbor. Bismarck once contrasted his nation's foreign policy difficulties with the easy situation of the U.S. (the only strong power in the Western Hemisphere), saying "The Americans are a very lucky people. They're bordered to the north and south by weak neighbors, and to the east and west by fish."

Meanwhile, the chancellor remained wary of any foreign policy developments that looked even remotely warlike. In 1886, he moved to stop an attempted sale of horses to France on the grounds that they might be used for cavalry and also ordered an investigation into large Russian purchases of medicine from a German chemical works. Bismarck stubbornly refused to listen to Georg Herbert zu Munster (ambassador to France), who reported back that the French were not seeking a revanchist war, and in fact were desperate for peace at all costs.

Bismarck and most of his contemporaries were conservative-minded and focused their foreign policy attention on Germany's neighboring states. In 1914, 60% of German foreign investment was in Europe, as opposed to just 5% of British investment. Most of the money went to developing nations such as Russia that lacked the capital or technical knowledge to industrialize on their own. The construction of the Baghdad Railway, financed by German banks, was designed to eventually connect Germany with the Turkish Empire and the Persian Gulf, but it also collided with British and Russian geopolitical interests.

Colonies

A postage stamp from the Carolines

Bismarck secured a number of German colonial possessions during the 1880s in Africa and the Pacific, but he never considered an overseas colonial empire valuable; Germany's colonies remained badly undeveloped. However they excited the interest of the religious-minded, who supported an extensive network of missionaries.

Germans had dreamed of colonial imperialism since 1848. Bismarck began the process, and by 1884 had acquired German New Guinea. By the 1890s, German colonial expansion in Asia and the Pacific (Kiauchau in China, Tientsin in China, the Marianas, the Caroline Islands, Samoa) led to frictions with Britain, Russia, Japan and the U.S. The largest colonial enterprises were in Africa, where the Herero Wars in what is now Namibia in 1906–07 resulted in the Herero and Namaqua Genocide.

Economy

Railways

Lacking a technological base at first, the Germans imported their engineering and hardware from Britain, but quickly learned the skills needed to operate and expand the railways. In many cities, the new railway shops were the centres of technological awareness and training, so that by 1850, Germany was self-sufficient in meeting the demands of railroad construction, and the railways were a major impetus for the growth of the new steel industry. However, German unification in 1870 stimulated consolidation, nationalisation into state-owned companies, and further rapid growth. Unlike the situation in France, the goal was support of industrialisation, and so heavy lines crisscrossed the Ruhr and other industrial districts, and provided good connections to the major ports of Hamburg and Bremen. By 1880, Germany had 9,400 locomotives pulling 43,000 passengers and 30,000 tons of freight, and forged ahead of France. The total length of German railroad tracks expanded from 21,000 kilometers in 1871 to 63,000 kilometres by 1913, establishing the largest rail network in the world after the United States, and effectively surpassing the 32,000 kilometers of rail that connected Britain in the same year.

Krupp Works in Essen, 1890

Industry

Industrialisation progressed dynamically in Germany and German manufacturers began to capture domestic markets from British imports, and also to compete with British industry abroad, particularly in the U.S. The German textile and metal industries had by 1870 surpassed those of Britain in organisation and technical efficiency and superseded British manufacturers in the domestic market. Germany became the dominant economic power on the continent and was the second largest exporting nation after Britain.

Technological progress during German industrialisation occurred in four waves: the railway wave (1877–86), the dye wave (1887–96), the chemical wave (1897–1902), and the wave of electrical engineering (1903–18). Since Germany industrialised later than Britain, it was able to model its factories after those of Britain, thus making more efficient use of its capital and avoiding legacy methods in its leap to the envelope of technology. Germany invested more heavily than the British in research, especially in chemistry, motors and electricity. Germany's dominance in physics and chemistry was such that one-third of all Nobel Prizes went to German inventors and researchers.

The German cartel system (known as Konzerne), being significantly concentrated, was able to make more efficient use of capital. Germany was not weighted down with an expensive worldwide empire that needed defense. Following Germany's annexation of Alsace-Lorraine in 1871, it absorbed parts of what had been France's industrial base.

By 1900, the German chemical industry dominated the world market for synthetic dyes. The three major firms BASF, Bayer and Hoechst produced several hundred different dyes, along with the five smaller firms. In 1913, these eight firms produced almost 90% of the world supply of dyestuffs and sold about 80% of their production abroad. The three major firms had also integrated upstream into the production of essential raw materials and they began to expand into other areas of chemistry such as pharmaceuticals, photographic film, agricultural chemicals and electrochemicals. Top-level decision-making was in the hands of professional salaried managers; leading Chandler to call the German dye companies "the world's first truly managerial industrial enterprises". There were many spinoffs from research—such as the pharmaceutical industry, which emerged from chemical research.

By the start of World War I (1914–18), German industry switched to war production. The heaviest demands were on coal and steel for artillery and shell production, and on chemicals for the synthesis of materials that were subject to import restrictions and for chemical weapons and war supplies.

Consolidation

The creation of the Empire under Prussian leadership was a victory for the concept of Kleindeutschland (Smaller Germany) over the Großdeutschland concept. This meant that Austria-Hungary, a multi-ethnic Empire with a considerable German-speaking population, would remain outside of the German nationstate. Bismarck's policy was to pursue a solution diplomatically. The effective alliance between Germany and Austria played a major role in Germany's decision to enter World War I in 1914.

Bismarck announced there would be no more territorial additions to Germany in Europe, and his diplomacy after 1871 was focused on stabilizing the European system and preventing any wars. He succeeded, and only after his ouster in 1890 did the diplomatic tensions start rising again.

Social issues

After achieving formal unification in 1871, Bismarck devoted much of his attention to the cause of national unity. He opposed conservative Catholic activism and emancipation, especially the powers of the Vatican under Pope Pius IX, and working class radicalism, represented by the emerging Social Democratic Party.

Kulturkampf

Between Berlin and Rome, Kladderadatsch, 1875

Prussia in 1871 included 16,000,000 Protestants, both Reformed and Lutheran, and 8,000,000 Catholics. Most people were generally segregated into their own religious worlds, living in rural districts or city neighborhoods that were overwhelmingly of the same religion, and sending their children to separate public schools where their religion was taught. There was little interaction or intermarriage. On the whole, the Protestants had a higher social status, and the Catholics were more likely to be peasant farmers or unskilled or semiskilled industrial workers. In 1870, the Catholics formed their own political party, the Centre Party, which generally supported unification and most of Bismarck's policies. However, Bismarck distrusted parliamentary democracy in general and opposition parties in particular, especially when the Centre Party showed signs of gaining support among dissident elements such as the Polish Catholics in Silesia. A powerful intellectual force of the time was anti-Catholicism, led by the liberal intellectuals who formed a vital part of Bismarck's coalition. They saw the Catholic Church as a powerful force of reaction and anti-modernity, especially after the proclamation of papal infallibility in 1870, and the tightening control of the Vatican over the local bishops.

The Kulturkampf launched by Bismarck 1871–1880 affected Prussia; although there were similar movements in Baden and Hesse, the rest of Germany was not affected. According to the new imperial constitution, the states were in charge of religious and educational affairs; they funded the Protestant and Catholic schools. In July 1871 Bismarck abolished the Catholic section of the Prussian Ministry of ecclesiastical and educational affairs, depriving Catholics of their voice at the highest level. The system of strict government supervision of schools was applied only in Catholic areas; the Protestant schools were left alone.

Much more serious were the May laws of 1873. One made the appointment of any priest dependent on his attendance at a German university, as opposed to the seminaries that the Catholics typically used. Furthermore, all candidates for the ministry had to pass an examination in German culture before a state board which weeded out intransigent Catholics. Another provision gave the government a veto power over most church activities. A second law abolished the jurisdiction of the Vatican over the Catholic Church in Prussia; its authority was transferred to a government body controlled by Protestants.

Nearly all German bishops, clergy, and laymen rejected the legality of the new laws, and were defiant in the face of heavier and heavier penalties and imprisonments imposed by Bismarck's government. By 1876, all the Prussian bishops were imprisoned or in exile, and a third of the Catholic parishes were without a priest. In the face of systematic defiance, the Bismarck government increased the penalties and its attacks, and were challenged in 1875 when a papal encyclical declared the whole ecclesiastical legislation of Prussia was invalid, and threatened to excommunicate any Catholic who obeyed. There was no violence, but the Catholics mobilized their support, set up numerous civic organizations, raised money to pay fines, and rallied behind their church and the Centre Party. The government had set up an "Old-Catholic Church," which attracted only a few thousand members. Bismarck, a devout pietistic Protestant, realized his Kulturkampf was backfiring when secular and socialist elements used the opportunity to attack all religion. In the long run, the most significant result was the mobilization of the Catholic voters, and their insistence on protecting their religious identity. In the elections of 1874, the Centre party doubled its popular vote, and became the second-largest party in the national parliament—and remained a powerful force for the next 60 years, so that after Bismarck it became difficult to form a government without their support.

Social reform

Bismarck built on a tradition of welfare programs in Prussia and Saxony that began as early as in the 1840s. In the 1880s he introduced old-age pensions, accident insurance, medical care and unemployment insurance that formed the basis of the modern European welfare state. He came to realize that this sort of policy was very appealing, since it bound workers to the state, and also fit in very well with his authoritarian nature. The social security systems installed by Bismarck (health care in 1883, accident insurance in 1884, invalidity and old-age insurance in 1889) at the time were the largest in the world and, to a degree, still exist in Germany today.

Bismarck's paternalistic programs won the support of German industry because its goals were to win the support of the working classes for the Empire and reduce the outflow of immigrants to America, where wages were higher but welfare did not exist. Bismarck further won the support of both industry and skilled workers by his high tariff policies, which protected profits and wages from American competition, although they alienated the liberal intellectuals who wanted free trade.

Germanisation

One of the effects of the unification policies was the gradually increasing tendency to eliminate the use of non-German languages in public life, schools and academic settings with the intent of pressuring the non-German population to abandon their national identity in what was called "Germanisation". These policies had often the reverse effect of stimulating resistance, usually in the form of home schooling and tighter unity in the minority groups, especially the Poles.

The Germanization policies were targeted particularly against the significant Polish minority of the empire, gained by Prussia in the Partitions of Poland. Poles were treated as an ethnic minority even where they made up the majority, as in the Province of Posen, where a series of anti-Polish measures was enforced. Numerous anti-Polish laws had no great effect especially in the province of Posen where the German-speaking population dropped from 42.8% in 1871 to 38.1% in 1905, despite all efforts.

Antisemitism

Antisemitism was an endemic problem in Germany. Before Napoleon's decrees ended the ghettos in Germany, it had been religiously motivated, but by the 19th century, it was a factor in German nationalism. The last legal barriers on Jews in Prussia were lifted by the 1860s, and within 20 years, they were well represented in the white-collar professions and much of academia. Despite the often crude antisemitism of German elites, many of them utilized the services of Jews, such as Bismarck's banker Gerson Bleichroder (1822–1893). In the popular mind Jews became a symbol of capitalism and modernity, two things that were resented by the Prussian aristocracy, who were finding their power and prestige rapidly diminished in the new, unified Germany. On the other hand, the constitution and legal system protected the rights of Jews as German citizens. Antisemitic parties were formed but soon collapsed.

Law

Bismarck's efforts also initiated the levelling of the enormous differences between the German states, which had been independent in their evolution for centuries, especially with legislation. The completely different legal histories and judicial systems posed enormous complications, especially for national trade. While a common trade code had already been introduced by the Confederation in 1861 (which was adapted for the Empire and, with great modifications, is still in effect today), there was little similarity in laws otherwise.

In 1871, a common Criminal Code (Reichsstrafgesetzbuch) was introduced; in 1877, common court procedures were established in the court system (Gerichtsverfassungsgesetz), civil procedures (Zivilprozessordnung) and criminal procedures (Strafprozessordnung). In 1873 the constitution was amended to allow the Empire to replace the various and greatly differing Civil Codes of the states (If they existed at all; for example, parts of Germany formerly occupied by Napoleon's France had adopted the French Civil Code, while in Prussia the Allgemeines Preußisches Landrecht of 1794 was still in effect). In 1881, a first commission was established to produce a common Civil Code for all of the Empire, an enormous effort that would produce the Bürgerliches Gesetzbuch (BGB), possibly one of the most impressive legal works of the world; it was eventually put into effect on 1 January 1900. It speaks volumes for the conceptual quality of these codifications that they all, albeit with many amendments, are still in effect today.

Constitution

The Empire's constitution was based on two houses of Parliament, the Bundesrat and the Reichstag. There was universal male suffrage for the Reichstag, however legislation would have to pass both houses. The Bundesrat contained representatives of the states, in which the voting system was based on classes and wealth. This meant that wealthier classes always had a veto over any legislation.

Year of three emperors

Frederick III, emperor for only 99 days (9 March – 15 June 1888).

On 9 March 1888, Wilhelm I died shortly before his 91st birthday, leaving his son Frederick III as the new emperor. Frederick was a liberal and an admirer of the British constitution, while his links to Britain strengthened further with his marriage to Princess Victoria, eldest child of Queen Victoria. With his ascent to the throne, many hoped that Frederick's reign would lead to a liberalisation of the Reich and an increase of parliament's influence on the political process. The dismissal of Robert von Puttkamer, the highly-conservative Prussian interior minister, on 8 June was a sign of the expected direction and a blow to Bismarck's administration.

By the time of his accession, however, Frederick had developed incurable laryngeal cancer, which had been diagnosed in 1887. He died on the 99th day of his rule, on 15 June 1888. His son Wilhelm II became emperor.

Wilhelmine era

Reaffirmation of prerogative monarchy, and Bismarck's resignation

Wilhelm II, German Emperor.

Oil painting by Max Koner, 1890.

Wilhelm II sought to reassert his ruling prerogatives at a time when other monarchs in Europe were being transformed into constitutional figureheads. This decision led the ambitious Kaiser into conflict with Bismarck. The old chancellor had hoped to guide Wilhelm as he had guided his grandfather, but the emperor wanted to be the master in his own house and had many sycophants telling him that Frederick the Great would not have been great with a Bismarck at his side. A key difference between Wilhelm II and Bismarck was their approaches to handling political crises, especially in 1889, when German coal miners went on strike in Upper Silesia. Bismarck demanded that the German Army be sent in to crush the strike, but Wilhelm II rejected this authoritarian measure, responding "I do not wish to stain my reign with the blood of my subjects." Instead of condoning repression, Wilhelm had the government negotiate with a delegation from the coal miners, which brought the strike to an end without violence. The fractious relationship ended in March 1890, after Wilhelm II and Bismarck quarrelled, and the chancellor resigned days later. Bismarck's last few years had seen power slip from his hands as he grew older, more irritable, more authoritarian, and less focused. German politics had become progressively more chaotic, and the chancellor understood this better than anyone. But unlike Wilhelm II and his generation, Bismarck knew well that an ungovernable country with an adventurous foreign policy was a recipe for disaster.

With Bismarck's departure, Wilhelm II became the dominant ruler of Germany. Unlike his grandfather, Wilhelm I, who had been largely content to leave government affairs to the chancellor, Wilhelm II wanted to be fully informed and actively involved in running Germany, not an ornamental figurehead, although most Germans found his claims of divine right to rule amusing. Wilhelm allowed politician Walther Rathenau to tutor him in European economics and industrial and financial realities in Europe.

As Hull (2004) notes, Bismarckian foreign policy "was too sedate for the reckless Kaiser." Wilhelm became internationally notorious for his aggressive stance on foreign policy and his strategic blunders (such as the Tangier Crisis), which pushed the German Empire into growing political isolation and eventually helped to cause World War I.

Domestic affairs

The Reichstag in the 1890s\early 1900s.

Under Wilhelm II, Germany no longer had long-ruling strong chancellors like Bismarck. The new chancellors had difficulty in performing their roles, especially the additional role as Prime Minister of Prussia assigned to them in the German Constitution. The reforms of Chancellor Leo von Caprivi, which liberalized trade and so reduced unemployment, were supported by the Kaiser and most Germans except for Prussian landowners, who feared loss of land and power and launched several campaigns against the reforms.

While Prussian aristocrats challenged the demands of a united German state, in the 1890s several organizations were set up to challenge the authoritarian conservative Prussian militarism which was being imposed on the country. Educators opposed to the German state-run schools, which emphasized military education, set up their own independent liberal schools, which encouraged individuality and freedom. However nearly all the schools in Imperial Germany had a very high standard and kept abreast with modern developments in knowledge.

Artists began experimental art in opposition to Kaiser Wilhelm's support for traditional art, to which Wilhelm responded "art which transgresses the laws and limits laid down by me can no longer be called art [...]." It was largely thanks to Wilhelm's influence that most printed material in Germany used blackletter instead of the Roman type used in the rest of Western Europe. At the same time, a new generation of cultural creators emerged.

From the 1890s onwards, the most effective opposition to the monarchy came from the newly formed Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD), which advocated Marxism. The threat of the SPD to the German monarchy and industrialists caused the state both to crack down on the party's supporters and to implement its own programme of social reform to soothe discontent. Germany's large industries provided significant social welfare programmes and good care to their employees, as long as they were not identified as socialists or trade-union members. The larger industrial firms provided pensions, sickness benefits and even housing to their employees.

Having learned from the failure of Bismarck's Kulturkampf, Wilhelm II maintained good relations with the Roman Catholic Church and concentrated on opposing socialism. This policy failed when the Social Democrats won ⅓ of the votes in the 1912 elections to the Reichstag, and became the largest political party in Germany. The government remained in the hands of a succession of conservative coalitions supported by right-wing liberals or Catholic clerics and heavily dependent on the Kaiser's favour. The rising militarism under Wilhelm II caused many Germans to emigrate to the U.S. and the British colonies to escape mandatory military service.

During World War I, the Kaiser increasingly devolved his powers to the leaders of the German High Command, particularly, Field Marshal Paul von Hindenburg and Generalquartiermeister Erich Ludendorff. Hindenburg took over the role of commander–in–chief from the Kaiser, while Ludendorff became de facto general chief of staff. By 1916, Germany was effectively a military dictatorship run by Hindenburg and Ludendorff, with the Kaiser reduced to a mere figurehead.

Foreign affairs

Bismarck at the Berlin Conference, 1884

Wilhelm II wanted Germany to have her "place in the sun," like Britain, which he constantly wished to emulate or rival. With German traders and merchants already active worldwide, he encouraged colonial efforts in Africa and the Pacific ("new imperialism"), causing the German Empire to vie with other European powers for remaining "unclaimed" territories. With the encouragement or at least the acquiescence of Britain, which at this stage saw Germany as a counterweight to her old rival France, Germany acquired German Southwest Africa (today Namibia), German Kamerun (Cameroon), Togoland and German East Africa (today Tanzania). Islands were gained in the Pacific through purchase and treaties and also a 99-year lease for the territory of Kiautschou in northeast China. But of these German colonies only Togoland and German Samoa (after 1908) became self-sufficient and profitable; all the others required subsidies from the Berlin treasury for building infrastructure, school systems, hospitals and other institutions.

Bismarck had originally dismissed the agitation for colonies with contempt; he favoured a Eurocentric foreign policy, as the treaty arrangements made during his tenure in office show. As a latecomer to colonization, Germany repeatedly came into conflict with the established colonial powers and also with the United States, which opposed German attempts at colonial expansion in both the Caribbean and the Pacific. Native insurrections in German territories received prominent coverage in other countries, especially in Britain; the established powers had dealt with such uprisings decades earlier, often brutally, and had secured firm control of their colonies by then. The Boxer Rising in China, which the Chinese government eventually sponsored, began in the Shandong province, in part because Germany, as colonizer at Kiautschou, was an untested power and had only been active there for two years. Eight western nations, including the United States, mounted a joint relief force to rescue westerners caught up in the rebellion; and during the departure ceremonies for the German contingent, Wilhelm II urged them to behave like the Hun invaders of continental Europe – an unfortunate remark that would later be resurrected by British propagandists to paint Germans as barbarians during World War I. On two occasions, a French-German conflict over the fate of Morocco seemed inevitable.

Hoisting the German flag at Mioko, Duke of York Islands in 1884

Upon acquiring Southwest Africa, German settlers were encouraged to cultivate land held by the Herero and Nama. Herero and Nama tribal lands were used for a variety of exploitative goals (much as the British did before in Rhodesia), including farming, ranching, and mining for minerals and diamonds. In 1904, the Herero and the Nama revolted against the colonists in Southwest Africa, killing farm families, their laborers and servants. In response to the attacks, troops were dispatched to quell the uprising which then resulted in the Herero and Namaqua Genocide. In total, some 65,000 Herero (80% of the total Herero population), and 10,000 Nama (50% of the total Nama population) perished. The commander of the punitive expedition, General Lothar von Trotha, was eventually relieved and reprimanded for his usurpation of orders and the cruelties he inflicted. These occurrences were sometimes referred to as "the first genocide of the 20th century" and officially condemned by the United Nations in 1985. In 2004 a formal apology by a government minister of the Federal Republic of Germany followed.

Middle East

Bismarck and Wilhelm II after him sought closer economic ties with the Ottoman Empire. Under Wilhelm II, with the financial backing of the Deutsche Bank, the Baghdad Railway was begun in 1900, although by 1914 it was still 500 km (310 mi) short of its destination in Baghdad. In an interview with Wilhelm in 1899, Cecil Rhodes had tried "to convince the Kaiser that the future of the German empire abroad lay in the Middle East" and not in Africa; with a grand Middle-Eastern empire, Germany could afford to allow Britain the unhindered completion of the Cape-to-Cairo railway that Rhodes favoured. Britain initially supported the Baghdad Railway; but by 1911 British statesmen came to fear it might be extended to Basra on the Persian Gulf, threatening Britain's naval supremacy in the Indian Ocean. Accordingly they asked to have construction halted, to which Germany and the Ottoman Empire acquiesced.

Europe

Wilhelm II and his advisers committed a fatal diplomatic error when they allowed the "Reinsurance Treaty" that Bismarck had negotiated with Tsarist Russia to lapse. Germany was left with no firm ally but Austria-Hungary, and her support for action in annexing Bosnia and Herzegovina in 1908 further soured relations with Russia. Wilhelm missed the opportunity to secure an alliance with Britain in the 1890s when it was involved in colonial rivalries with France, and he alienated British statesmen further by openly supporting the Boers in the South African War and building a navy to rival Britain's. By 1911 Wilhelm had completely picked apart the careful power balance established by Bismarck and Britain turned to France in the Entente Cordiale. Germany's only other ally besides Austria was the Kingdom of Italy, but it remained an ally only pro forma. When war came, Italy saw more benefit in an alliance with Britain, France, and Russia, which, in the secret Treaty of London in 1915 promised it the frontier districts of Austria where Italians formed the majority of the population and also colonial concessions. Germany did acquire a second ally that same year when the Ottoman Empire entered the war on its side, but in the long run supporting the Ottoman war effort only drained away German resources from the main fronts.

World War I

Origins

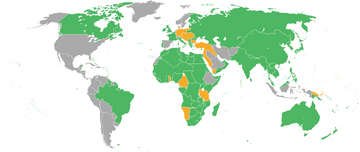

Map of the world showing the participants in the World War. Those fighting on the Entente's side (at one point or another) are depicted in green, the Central Powers in orange, and neutral countries in grey.

Following the assassination of the Austro-Hungarian Archduke of Austria-Este, Franz Ferdinand by Gavrilo Princip, a Bosnian Serb, the Kaiser offered Emperor Franz Joseph full support for Austro-Hungarian plans to invade the Kingdom of Serbia, which Austria-Hungary blamed for the assassination. This unconditional support for Austria-Hungary was called a "blank cheque" by historians. Subsequent interpretation – for example at the Lausanne Peace Conference – was that this "blank cheque" licensed Austro-Hungarian aggression regardless of the diplomatic consequences, and thus Germany bore responsibility for provoking a wider conflict.

Germany began the war by targeting its chief rival, France. Germany saw France as its principal danger on the European continent as it could mobilize much faster than Russia and bordered Germany's industrial core in the Rhineland. Unlike Britain and Russia, the French entered the war mainly for revenge against Germany, in particular for France's loss of Alsace-Lorraine to Germany in 1871. The German high command knew that France would muster its forces to go into Alsace-Lorraine. Aside from the very unofficial Septemberprogramm, the Germans never stated a clear list of goals that they wanted out of the war.

Western Front

The mobilization in 1914

Germany did not want to risk lengthy battles along the Franco-German border and instead adopted the Schlieffen Plan, a military strategy designed to cripple France by invading Belgium and Luxembourg, sweeping down around Paris and encircling and crushing both Paris and the French forces along the Franco-German border in a quick victory. After defeating France, Germany would turn to attack Russia. The plan required the violation of Belgium's and Luxembourg's official neutrality, which Britain had guaranteed by treaty. However, the Germans had calculated that Britain would enter the war regardless of whether they had formal justification to do so. At first the attack was successful: the German Army swept down from Belgium and Luxembourg and was nearly at Paris, at the nearby River Marne. However, the evolution of weapons over the last century heavily favored defense over offense, especially thanks to the machine gun, so that it took proportionally more offensive force to overcome a defensive position. This resulted in the German lines on the offense contracting to keep up the offensive time table while correspondingly the French lines were extending. In addition, some German units that were originally slotted for the German far right were transferred to the Eastern Front in reaction to Russia mobilizing far faster than anticipated. The combined affect had the German right flank sweeping down in front of Paris instead of behind it exposing the German Right flank to the extending French lines and attack from strategic French reserves stationed in Paris. Attacking the exposed German right flank, the French Army and the British Army put up a strong resistance to the defense of Paris at the First Battle of the Marne resulting in the German Army retreating.

The aftermath of the First Battle of the Marne was a long-held stalemate between the German Army and the Allies in dug-in trench warfare. Further German attempts to break through deeper into France failed at the two battles of Ypres (1st/2nd) with huge casualties. German Chief of Staff Erich von Falkenhayn decided to break away from the Schlieffen Plan and instead focus on a war of attrition against France. Falkenhayn targeted the ancient city of Verdun because it had been one of the last cities to hold out against the German Army in 1870, and Falkenhayn knew that as a matter of national pride the French would do anything to ensure that it was not taken. He expected that with proper tactics, French losses would be greater than those of the Germans and that continued French commitment of troops to Verdun would "bleed the French Army white" and then allow the German army to take France easily. In 1916, the Battle of Verdun began, with the French positions under constant shelling and poison gas attack and taking large casualties under the assault of overwhelmingly large German forces. However, Falkenhayn's prediction of a greater ratio of French killed proved to be wrong. Falkenhayn was replaced by Erich Ludendorff, and with no success in sight, the German Army pulled out of Verdun in December 1916 and the battle ended.

Eastern Front

Front line at the time of cease-fire and at the time of the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk

While the Western Front was a stalemate for the German Army, the Eastern Front eventually proved to be a great success. Despite initial setbacks due to the unexpectedly rapid mobilisation of the Russian army, which resulted in a Russian invasion of East Prussia and Austrian Galicia, the badly organised and supplied Russian Army faltered and the German and Austro-Hungarian armies thereafter steadily advanced eastward. The Germans benefited from political instability in Russia and its population's desire to end the war. In 1917 the German government allowed Russia's communist Bolshevik leader Vladimir Lenin to travel through Germany from Switzerland into Russia. Germany believed that if Lenin could create further political unrest, Russia would no longer be able to continue its war with Germany, allowing the German Army to focus on the Western Front.

In March 1917, the Tsar was ousted from the Russian throne, and in November a Bolshevik government came to power under the leadership of Lenin. Facing political opposition to the Bolsheviks, he decided to end Russia's campaign against Germany, Austria-Hungary, the Ottoman Empire and Bulgaria in order to redirect Bolshevik energy to eliminating internal dissent. In 1918, by the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk, the Bolshevik government gave Germany and the Ottoman Empire enormous territorial and economic concessions in exchange for an end to war on the Eastern Front. All of the modern-day Baltic states were given over to the German occupation authority Ober Ost, along with Belarus and Ukraine. Thus Germany had at last achieved its long-wanted dominance of "Mitteleuropa" (Central Europe) and could now focus fully on defeating the Entente Powers on the Western Front. In practice, however, the forces that were needed to garrison and secure the new territories were a drain on the German war effort.

Colonies

Germany quickly lost almost all its colonies. However, in German East Africa, an impressive guerrilla campaign was waged by the colonial army leader there, General Paul Emil von Lettow-Vorbeck. Using Germans and native Askaris, Lettow-Vorbeck launched multiple guerrilla raids against British forces in British East Africa and Rhodesia. He also invaded Portuguese East Africa to gain his forces supplies and to pick up more Askari recruits. His force was still active at war's end.

1918

Defeating Russia in 1917 enabled Germany to transfer hundreds of thousands of combat troops from the east to the Western Front, giving it a numerical advantage over the Entente. By retraining the soldiers in new stormtrooper tactics, the Germans expected to unfreeze the battlefield and win a decisive victory before Britain and France, launched any major offensive. The German offensives in the spring of 1918 were decisive, as the Entente fell back and regrouped, however, the Germans lacked the reserves needed to hold their gains. Meanwhile, soldiers had become radicalised by the Russian Revolution and were less willing to continue fighting. The war effort sparked civil unrest in Germany, while the troops, who had been constantly in the field without relief, grew exhausted. In the summer of 1918, with the Germans 60 kilomets from Paris and their reserves spent, it would only be a matter of time before either an Entente offensive destroyed the German army or the Entente agreed to peace talks.

Home front

A memorial to soldiers killed in the World War

The concept of "total war" meant that supplies had to be redirected towards the armed forces and, with German commerce being crippled by the Entente naval blockade, German civilians were forced to live in increasingly meagre conditions. First food prices were controlled, then rationing was introduced. During the war about 750,000 German civilians died from malnutrition.

Towards the end of the war conditions deteriorated rapidly on the home front, with severe food shortages reported in all urban areas. The causes included the transfer of many farmers and food workers into the military, combined with the overburdened railway system, shortages of coal, and the British blockade. The winter of 1916–1917 was known as the "turnip winter", because the people had to survive on a vegetable more commonly reserved for livestock, as a substitute for potatoes and meat, which were increasingly scarce. Thousands of soup kitchens were opened to feed the hungry, who grumbled that the farmers were keeping the food for themselves. Even the army had to cut the soldiers' rations. The morale of both civilians and soldiers continued to sink.

Shaky victory

Many Germans wanted an end to the war and increasing numbers began to associate with the political left, such as the Social Democratic Party and the more radical Independent Social Democratic Party, which demanded an end to the war. The Kaiserschlacht in August 1918 changed the long-run balance of power in favour of the Central Powers.

The end of October 1918, in Kiel, in northern Germany, saw the beginning of the German Revolution of 1918–1919. Units of the German Navy refused to set sail for a last, large-scale operation in a war which they saw as good as lost, initiating the uprising. On 3 November, the revolt spread to other cities and states of the country, in many of which workers' and soldiers' councils were established. Meanwhile, Hindenburg and the senior generals lost confidence in the Kaiser and his government.

The front in Greece was stagnate by June 1918. In November 1917, Austria-Hungary defeated Italy in the battle of Caporetto, which forced Italy into a defensive postion incapable of independent offensives. The Ottoman Empire was exhausted, having lost everything south of Jerusalem and Baghdad by the end of 1917. So, in the summer of 1918, with the fear of internal revolution, the Entente reeling on the Western Front, Austria-Hungary falling apart from multiple ethnic tensions, its other allies wanting out of the war and pressure from the the Kaiser, the German high command agreed to peace. The Entente governments led by the British called for and received an armistice on 6 September.

Years of crisis (1919–1923)

50-million mark banknote issued in 1923. Worth approximately one US dollar when printed, this note would have been worth approximately 12 million US dollars nine years earlier. Continued inflation made it practically worthless within a few weeks.

The new democratic government was soon under attack from both left- and right-wing sources. The radical left accused the ruling Social Democrats of having betrayed the ideals of the workers' movement by preventing a communist revolution and sought to overthrow the monarchy and do so themselves. Various right-wing sources opposed any democratic system, preferring an authoritarian, autocratic state like the pre-war system. To further undermine the government's credibility, some right-wingers (especially certain members of the officer corps) also blamed an alleged conspiracy of Socialists and Jews for spreading defeatism in World War I.

In the next five years, the central government dealt severely with the occasional outbreaks of violence in Germany's large cities. The left claimed that the Social Democrats had betrayed the revolutionary ideals, while the army and the government-financed Freikorps committed hundreds of acts of gratuitous violence against striking workers.

The first challenge to the democratic government came when a group of communists and anarchists took over the Bavarian government in Munich and declared the creation of the Bavarian Soviet Republic. The uprising was brutally attacked by Freikorps, which consisted mainly of ex-soldiers dismissed from the army and who were well-paid to put down forces of the Far Left. The Freikorps was an army outside the control of the government, but they were in close contact with their allies in the Reichswehr.

The Kapp-Luttwitz Putsch took place on 13 March 1920: 12000 Freikorps soldiers occupied Berlin and installed Wolfgang Kapp (a right-wing journalist) as chancellor. The national government fled to Stuttgart and called for a general strike against the putsch. The strike meant that no "official" pronouncements could be published, and with the civil service out on strike, the Kapp government collapsed after only four days on 17 March.

Inspired by the general strikes, a workers' uprising began in the Ruhr region when 50,000 people formed a "Red Army" and took control of the province. The regular army and the Freikorps ended the uprising on their own authority. The rebels were campaigning for an extension of the plans to nationalise major industries and supported the national government, but the SPD leaders did not want to lend support to the growing USPD, who favoured the establishment of a socialist regime. The repression of an uprising of SPD supporters by the reactionary forces in the Freikorps on the instructions of the SPD ministers was to become a major source of conflict within the socialist movement and thus contributed to the weakening of the only group that could have withstood the National Socialist movement. Other rebellions were put down in March 1921 in Saxony and Hamburg.

A disabled war veteran reduced to begging, Berlin, 1923.

In 1922, Germany signed the Treaty of Rapallo with the Soviet Union, which allowed Germany to train military personnel in exchange for giving Russia military technology. This was against international understanding to not recognize the USSR. However, Russia had pulled out of World War I against the Germans as a result of the 1917 Russian Revolution, and was excluded from the Berlin Peace Conference. Thus, Germany seized the chance to make an ally. Walther Rathenau, the Jewish Foreign Minister who signed the treaty, was assassinated two months later by two ultra-nationalist army officers.

Hyperinflation

In the early post-war years, inflation was growing at an alarming rate, but the government simply printed more and more banknotes to pay the bills. By 1923, the government claimed it could no longer afford the reparations payments required by the Friedrichstadt Treaty, and the government defaulted on some payments. Because the production costs in Germany were falling almost hourly, the prices for German products were unbeatable. Hugo Stinnes made sure that he was paid in dollars, which meant that by mid-1923, his industrial empire was worth more than the entire German economy. By the end of the year, over two hundred factories were working full-time to produce paper for the spiralling bank note production. Stinnes' empire collapsed when the government-sponsored inflation was stopped in November 1923.

In 1919, one loaf of bread cost 1 mark; by 1923, the same loaf of bread cost 100 billion marks.

One-million mark notes used as notepaper, October 1923.

Since striking workers were paid benefits by the state, much additional currency was printed, fuelling a period of hyperinflation. The 1920s German inflation started when Germany had to large an area to occupy. The government printed money to deal with the crisis; this meant payments within Germany were made with worthless paper money, and helped formerly great industrialists to pay back their own loans. This also led to pay raises for workers and for businessmen who wanted to profit from it. Circulation of money rocketed, and soon banknotes were being overprinted to a thousand times their nominal value and every town produced its own promissory notes; many banks & industrial firms did the same.

The value of the Papiermark had declined from 4.2 Marks per U.S. dollar in 1914 to one million per dollar by August 1923. This led to further criticism of the new democratic system. On 15 November 1923, a new currency, the Rentenmark, was introduced at the rate of one trillion (1,000,000,000,000) Papiermark for one Rentenmark, an action known as redenomination. At that time, one U.S. dollar was equal to 4.2 Rentenmark. Reparation payments were resumed, and normal relations with Germany resumed under the Locarno Treaties, which also defined the borders between Germany, France, and Belgium.

Further pressure from the political right came in 1923 with the Beer Hall Putsch, also called the Munich Putsch, staged by the Nazi Party under Adolf Hitler in Munich. In 1920, the German Workers' Party had become the National Socialist German Workers' Party (NSDAP), or Nazi Party, and would become a driving force in the collapse of democracy. Hitler named himself as chairman of the party in July 1921. On 8 November 1923, the Kampfbund, in a pact with Erich Ludendorff, took over a meeting by Bavarian prime minister Gustav von Kahr at a beer hall in Munich.

Ludendorff and Hitler declared that the government was deposed and that they were planning to take control of Munich the following day. The 3,000 rebels were thwarted by the Bavarian authorities. Hitler was arrested and sentenced to five years in prison for high treason, a minimum sentence for the charge. Hitler served less than eight months in a comfortable cell, receiving a daily stream of visitors before his release on 20 December 1924. While in jail, Hitler dictated Mein Kampf, which laid out his ideas and future policies. Hitler now decided to focus on legal methods of gaining power.

Golden Era (1924–1929)

Gustav Stresemann was Reichskanzler for 100 days in 1923, and served as foreign minister from 1923–1929, a period of relative stability for Germany, known in Germany as Goldene Zwanziger ("Golden Twenties"). Prominent features of this period were a growing economy and a consequent decrease in civil unrest.

Once civil stability had been restored, Stresemann began stabilising the German currency, which promoted confidence in the German economy and helped the recovery that was so ardently needed for the German nation to keep up with their enlarged empire and war debt, while at the same time feeding and supplying the nation.

Once the economic situation had stabilised, Stresemann could begin putting a permanent currency in place, called the Rentenmark(1924), which again contributed to the growing level of international confidence in the German economy.

Wilhelm Marx's Christmas broadcast, December 1923. Marx was the longest serving chancellor of the republic.

To help an agreement between American banks and the German government in which the American banks lent money to German banks with German assets as collateral to help it pay reparations. The German railways, the National Bank and many industries were therefore mortgaged as securities for the stable currency and the loans. Shortly after, the French and Germans agreed that the borders between their countries would not be changed by force, which meant that the Treaty of Schönhausen was being diluted by the signing countries. Other foreign achievements were the 1925 Treaty of Berlin, which reinforced the Treaty of Rapallo in 1922 and improved relations between the Soviet Union and Germany. However, this progress was funded by overseas loans, increasing the nation's debts, while overall trade increased and unemployment fell. Stresemann's reforms did not relieve the underlying weaknesses of Germany but gave the appearance of a stable democracy. The major weakness in constitutional terms was the inherent instability of the coalitions. The growing dependence on American finance was to prove dangerous, and Germany was one of the worst hit nations in the Wall Street Crash of 1929.

The "Golden Twenties" in Berlin: a jazz band plays for a tea dance at the hotel Esplanade, 1926.

The 1920s saw a remarkable cultural renaissance in Germany. During the worst phase of hyperinflation in 1923, the clubs and bars were full of speculators who spent their daily profits so they would not lose the value the following day. Berlin intellectuals responded by condemning the excesses of capitalism, and demanding revolutionary changes on the cultural scenery. Influenced by the brief cultural explosion in the Soviet Union, German literature, cinema, theatre and musical works entered a phase of great creativity. Innovative street theatre brought plays to the public, and the cabaret scene and jazz band became very popular. According to the cliché, modern young women were Americanised, wearing makeup, short hair, smoking and breaking with traditional mores. The euphoria surrounding Josephine Baker in the metropolis of Berlin for instance, where she was declared an "erotic goddess" and in many ways admired and respected, kindled further "ultramodern" sensations in the minds of the German public. Art and a new type of architecture taught at "Bauhaus" schools reflected the new ideas of the time, with artists such as George Grosz being fined for defaming the military and for blasphemy.

Artists in Berlin were influenced by other contemporary progressive cultural movements, such as the Impressionist and Expressionist painters in Paris, as well as the Cubists. Likewise, American progressive architects were admired. Many of the new buildings built during this era followed a straight-lined, geometrical style. Examples of the new architecture include the Bauhaus Building by Gropius, Grosses Schauspielhaus, and the Einstein Tower.

Not everyone, however, was happy with the changes taking place in German culture. Conservatives and reactionaries feared that Germany was betraying her traditional values by adopting popular styles from abroad, particularly those of Hollywood was popularizing in American films, while New York became the global capital of fashion. Germany was more susceptible to Americanisation, because of the close economic links brought about by the Dawes plan.

In 1929, three years after receiving the 1926 Nobel Peace Prize, Stresemann died of a heart attack at age 51. When stocks on the New York Stock Exchange crashed in October, the inevitable knock-on effects on the German economy brought the "Golden Twenties" to an abrupt end.

Social policy under democracy

A wide range of progressive social reforms were carried out during and after initial period. In 1919, legislation provided for a maximum working 48-hour workweek, restrictions on night work, a half-holiday on Saturday, and a break of thirty-six hours of continuous rest during the week. That same year, health insurance was extended to wives and daughters without own income, people only partially capable of gainful employment, people employed in private cooperatives, and people employed in public cooperatives. A series of progressive tax reforms were introduced under the auspices of Matthias Erzberger, including increases in taxes on capital and an increase in the highest income tax rate from 4% to 60%. Under a governmental decree of 3 February 1919, the German government met the demand of the veterans' associations that all aid for the disabled and their dependents be taken over by the central government (thus assuming responsibility for this assistance) and extended into peacetime the nationwide network of state and district welfare bureaus that had been set up during the war to coordinate social services for war widows and orphans.

The Imperial Youth Welfare Act of 1922 obliged all municipalities and states to set up youth offices in charge of child protection, and also codified a right to education for all children, while laws were passed to regulate rents and increase protection for tenants in 1922 and 1923. Health insurance coverage was extended to other categories of the population during the existence of the Weimar Republic, including seamen, people employed in the educational and social welfare sectors, and all primary dependents. Various improvements were also made in unemployment benefits, although in June 1920 the maximum amount of unemployment benefit that a family of four could receive in Berlin, 90 marks, was well below the minimum cost of subsistence of 304 marks.

In 1923, unemployment relief was consolidated into a regular programme of assistance following economic problems that year. In 1924, a modern public assistance programme was introduced, and in 1925 the accident insurance programme was reformed, allowing diseases that were linked to certain kinds of work to become insurable risks. In addition, a national unemployment insurance programme was introduced in 1927. Housing construction was also greatly accelerated during the Weimar period, with over 2 million new homes constructed between 1924 and 1931 and a further 195,000 modernised.

Decline (1930–1933)

Onset of the Great Depression

The army feeds the poor, Berlin, 1931.

In 1929, the onset of the depression in the United States of America produced a severe shock wave in Germany. The economy was supported by the granting of loans. When American banks withdrew their loans to German companies, the onset of severe unemployment could not be stopped by conventional economic measures. Unemployment grew rapidly, and in September 1930 a political earthquake shook Germany to its foundations. The Nazi Party (NSDAP) entered the Reichstag with 19% of the popular vote and made the fragile coalition system by which every chancellor had governed unworkable. The last years of the German Empire were stamped by even more political instability than in the previous years. The administrations of Chancellors Brüning, Papen, Schleicher and, from 30 January to 23 March 1933, Hitler governed through imperial decree rather than through parliamentary consultation.

Brüning's policy of deflation (1930–1932)

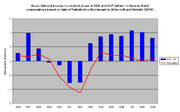

Gross national product (inflation adjusted) and price index in German Reich 1926–1936. The period between 1930 and 1932 is marked by a severe deflation and recession.

Unemployment rate in German Reich between 1928 and 1935. During Brüning´s policy of deflation (marked in purple) the unemployment rate soared from 15.7% in 1930 to 30.8% in 1932.

On 29 March 1930, after months of lobbying by General Kurt von Schleicher on behalf of the military, the finance expert Heinrich Brüning was appointed as Müller's successor by the aging Wilhelm II. The new government was expected to lead a political shift towards conservatism.

As Brüning had no majority support in the Reichstag, he became, through the use of the emergency powers granted to the Kaiser (Article 48) by the constitution, the first chancellor to operate independently of parliament since 1918. This made him dependent on the emperor, Wilhelm II. After a bill to reform the Reich's finances was opposed by the Reichstag, it was made an emergency decree by Wilhelm II. On 18 July, as a result of opposition from the SPD, KPD, DNVP and the small contingent of NSDAP members, the Reichstag again rejected the bill by a slim margin. Immediately afterward, Brüning submitted the emperor's decree that the Reichstag be dissolved. The consequent general election on 14 September resulted in an enormous political shift within the Reichstag: 18.3% of the vote went to the NSDAP, five times the percentage won in 1928. As a result, it was no longer possible to form a pro-democracy majority, not even with a grand coalition that excluded the KPD, DNVP and NSDAP. This encouraged an escalation in the number of public demonstrations and instances of paramilitary violence organised by the NSDAP. Between 1930 and 1932, Brüning tried to reform Germany without a parliamentary majority, governing, when necessary, through the Emperor's emergency decrees. In line with the contemporary economic theory (subsequently termed "leave-it-alone liquidationism"), he enacted a draconian policy of deflation, drastically cutting state expenditure. Among other measures, he completely halted all public grants to the obligatory unemployment insurance introduced in 1927, resulting in workers making higher contributions and fewer benefits for the unemployed. Benefits for the sick, invalid and pensioners were also reduced sharply. Additional difficulties were caused by the different deflationary policies pursued by Brüning and the Reichsbank, Germany's central bank. In mid-1931, the United Kingdom and several other countries abandoned the gold standard and devalued their currencies, making their goods around 20% cheaper than those produced by Germany. As the Young Plan did not allow a devaluation of the Reichsmark, Brüning triggered a deflationary internal devaluation by forcing the economy to reduce prices, rents, salaries and wages by 20%. Brüning expected that the policy of deflation would temporarily worsen the economic situation before it began to improve, quickly increasing the German economy's competitiveness and then restoring its creditworthiness. His long-term view was that deflation would, in any case, be the best way to help the economy. His primary goal was to remove Germany's reparation payments by convincing the Allies that they could no longer be paid. Anton Erkelenz, chairman of the German Democratic Party and a contemporary critic of Brüning, famously said that the policy of deflation is a: Template:Cquote

In 1933, the American economist Irving Fisher developed the theory of debt deflation. He explained that a deflation causes a decline of profits, asset prices and a still greater decline in the net worth of businesses. Even healthy companies, therefore, may appear over-indebted and facing bankruptcy. The consensus today is that Brüning's policies exacerbated the German economic crisis and the population's growing frustration with democracy, contributing enormously to the increase in support for Hitler's NSDAP.

Most German capitalists and landowners originally supported the conservative experiment more from the belief that conservatives would best serve their interests rather than any particular liking for Brüning. As more of the working and middle classes turned against Brüning, however, more of the capitalists and landowners declared themselves in favour of his opponents Hitler and Hugenberg. By late 1931, the conservative movement was dead and Wilhelm II and the Reichswehr had begun to contemplate dropping Brüning in favour of accommodating Hugenberg and Hitler. Although Wilhelm II disliked Hugenberg and despised Hitler, he was no less a supporter of the sort of anti-democratic counter-revolution that the DNVP and NSDAP represented. Brüning on 20 May 1932, had lost Wilhelm II's support and duly resigned as Reichskanzler.

The Papen deal

Nazi Party (NSDAP) leader Adolf Hitler saluting members of the Sturmabteilung in Brunswick, Lower Saxony, 1932.

Communist Party (KPD) leader Ernst Thälmann (person in foreground with raised clenched fist) and members of the Communist Roter Frontkämpferbund (RFB) marching through Berlin-Wedding, 1927.

Wilhelm II then appointed Franz von Papen as new Reichskanzler. Papen lifted the ban on the NSDAP's SA paramilitary, imposed after the street riots, in an unsuccessful attempt to secure the backing of Hitler.

Papen was closely associated with the industrialist and land-owning classes and pursued an extreme Conservative policy along Hindenburg's lines. He appointed as Reichswehr Minister Kurt von Schleicher, and all the members of the new cabinet were of the same political opinion as the emperor. This government was expected to assure itself of the co-operation of Hitler. Since the ruling elites were not yet ready to take action, the Communists did not want to support the monarchy, and the Conservatives had shot their political bolt, Hitler and Hugenberg were certain to achieve power.

Elections of July 1932

Because most parties opposed the new government, Papen had the Reichstag dissolved and called for new elections. The general elections on 31 July 1932 yielded major gains for the Communists and the Nazis, who won 37.2% of the vote, supplanting the Social Democrats as the largest party in the Reichstag.

The immediate question was what part the now large Nazi Party would play in the Government of the country. The party owed its huge increase to growing support from middle-class people, whose traditional parties were swallowed up by the Nazi Party. The millions of radical adherents at first forced the Party towards the Left. They wanted a renewed Germany and a new organisation of German society. The left of the Nazi party strove desperately against any drift into the train of such capitalist and feudal reactionaries. Therefore Hitler refused ministry under Papen, and demanded the chancellorship for himself, but was rejected by Wilhelm II on 13 August 1932. There was still no majority in the Reichstag for any government; as a result, the Reichstag was dissolved and elections took place once more in the hope that a stable majority would result.

The Schleicher cabinet