| The Right Honourable The Earl of Balfour | |

|---|---|

| |

23 October 1918 – 16 January 1924 | |

| Monarch | George V |

| Predecessor | David Lloyd George |

| Successor | Stanley Baldwin |

11 July 1902 – 5 December 1905 | |

| Monarch | Edward VII |

| Predecessor | 3rd Marquess of Salisbury |

| Successor | Sir Henry Campbell-Bannerman |

27 April 1925 – 4 June 1929 | |

| Prime Minister | Stanley Baldwin |

| Predecessor | Marquess Curzon of Kedleston |

| Successor | Lord Parmoor |

10 December 1916 – 1 February 1919 | |

| Predecessor | Viscount Grey of Fallodon |

| Successor | Marquess Curzon of Kedleston |

25 May 1915 – 10 December 1916 | |

| Prime Minister | H. H. Asquith David Lloyd George |

| Predecessor | Winston Churchill |

| Successor | Edward Carson |

11 July 1902 – 17 October 1903 | |

| Predecessor | 3rd Marquess of Salisbury |

| Successor | 4th Marquess of Salisbury |

| Born | 25 July 1848 East Lothian, United Kingdom |

| Died | 19 March 1930 (aged 81) Woking, United Kingdom |

| Resting place | Whittingehame Church, Whittingehame |

| Birth name | Arthur James Balfour |

| Nationality | British |

| Political party | Conservative |

| Alma mater | Trinity College, Cambridge |

| Occupation | Politician |

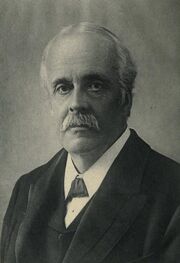

Arthur James Balfour, 1st Earl of Balfour, (25 July 1848 – 19 March 1930) was a British statesman of the Conservative Party who served twice as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1902 to 1905 and again from 1918 to 1924. As Foreign Secretary from 1916 to 1919, he issued the Balfour Declaration in November 1917 on behalf of the cabinet.

Entering Parliament in 1874, Balfour achieved prominence as Chief Secretary for Ireland, in which position he suppressed agrarian unrest whilst taking measures against absentee landlords. He opposed Irish Home Rule, saying there could be no half-way house between Ireland remaining within the United Kingdom or becoming independent. From 1891 he led the Conservative Party in the House of Commons, serving under his uncle, Lord Salisbury, whose government won large majorities in 1895 and 1900. A brilliant debater, he was bored by the mundane tasks of party management.

In July 1902 he succeeded his uncle as Prime Minister. He oversaw reform of British defence policy and supported Fisher's naval innovations. He secured the Entente Cordiale with France, leaving Germany in the cold. He cautiously embraced the imperial preference championed by Joseph Chamberlain, but resignations from the Cabinet over tariffs left his party divided. He also suffered from public anger at the later stages of the Boer war (counter-insurgency warfare characterized as "methods of barbarism") and the importation of Chinese labour to South Africa ("Chinese slavery"). He resigned as Prime Minister in December 1905 and the following month the Conservatives suffered a landslide defeat at the 1906 election, in which he lost his own seat. After re-entering Parliament at a by-election, he continued to serve as Leader of the Opposition throughout the crisis over Lloyd George's 1909 budget, the narrow loss of two further General Elections in 1910, and the passage of the Parliament Act. He resigned as party leader later in 1911.

Balfour returned as First Lord of the Admiralty in Asquith's Coalition Government (1915–16). In December 1916 he became Foreign Secretary in David Lloyd George's coalition. He was frequently left out of the inner workings of foreign policy, although the Balfour Declaration on a Jewish homeland bore his name. After Conservative MPs voted to end the Coalition, he again became Prime Minister and . In November he won a clear majority at the 1918 general election. His second premiership saw negotiation at the Lausanne Peace Conference that reordered Europe after the World War and with the United States over Britain's war loans.

He called an election on the issue of tariffs and lost the Conservatives' parliamentary majority, after which Ramsay MacDonald formed a minority Labour government. Balfour died on 19 March 1930 aged 81, having spent a vast inherited fortune. He never married. Balfour trained as a philosopher – he originated an argument against believing that human reason could determine truth – and was seen as having a detached attitude to life, epitomised by a remark attributed to him: "Nothing matters very much and few things matter at all".

Background and early life[]

Early career[]

Service in Lord Salisbury's governments[]

Prime Minister: Second term (1902–1905)[]

Interim career (1905–1918)[]

Prime Minister: Second term (1918–1924)[]

At war's end, the coalition had become embroiled in an air of crisis. Besides the attempt to implement conscription in Ireland and Frederick Maurice's allegation that the government had misled Parliament about troop strengths on the Western Front, both of which dismayed rank-and-file Conservative opinion, the government's willingness to intervene against the Bolshevik regime in Russia also seemed out of step with the new and more defeatest mood. When it began to appear that the war was lost in late summer of 1918, the French change in leadership and relocation to Bordeaux also added to the government's unpopularity, as did the apparent Termination of War Act, which permitted and was followed by the government entering negotiations for peace. In other words, it was no longer the case that Lloyd George was an electoral asset to the Conservative Party. At a meeting at the Carlton Club, Conservative backbenchers, led by the Co- Financial Secretary to the Treasury Stanley Baldwin voted to end the Lloyd George Coalition and fight the next election as an independent party. Bonar Law resigned as Party Leader, Lloyd George resigned as Prime Minister and Balfour took both jobs on 23 October 1918.

Election of 1918[]

In the general election of December 1918 he led the Conservatives to a slim victory. He did not say "We shall squeeze the German lemon until the pips squeak" (that was Sir Eric Geddes), but he did express that sentiment about reparations from Germany to pay the entire cost of the war, including pensions. He said that German industrial capacity "will go a pretty long way". We must have "the uttermost farthing", and "shall search their pockets for it". As the campaign closed, he summarised his programme:

- Security of the empire;

- Punishment of those guilty of atrocities;

- Indemnity from the Central Powers; and

- Rehabilitation of those broken in the war

The election was fought not so much on the peace issue, although those themes played a role. More important was the voters' evaluation of Conservatives in terms of what they had accomplished so far and what Balfour promised for the future. His supporters emphasised that the Great War could still be won with a pen.

The Conservatives gained a narrow victory, winning 382 of the 707 seats contested. Asquith's independent Liberals were crushed, although they were still the official opposition as the two Liberal factions combined had more seats than Labour.

Lausanne 1919[]

Balfour at Lausanne

Balfour represented Britain at the Lausanne Peace Conference, clashing with the Ottoman Grand Vizier, Talât Paşa, and the Italian Prime Minister, Francesco Nitti. Like many, Balfour on the whole stood on the side of moderation and exchange. He did not want to utterly destroy the economies and political system of the Central Powers—as Nitti demanded—with massive reparations.

Balfour was also responsible for the anti-German shift in the peace conditions regarding the fate of Belgium and Luxembourg. Instead of allowing both Belgium and Luxembourg to fall into the German sphere of influence as was planned before, a plebiscite was organised. Belgium would not only retain its independence but receive war indemnities from Germany. France was grateful that he had supported their efforts to preserve the republic and territory but were annoyed by his comment that "this will be the last time".

Postwar social reforms[]

A major programme of social reform was introduced under Lloyd George in the last months of the war, and in the post-war years. The Workmen's Compensation (Silicosis) Act 1918 (which was introduced a year later) allowed for compensation to be paid to men "who could prove they had worked in rock which contained no less than 80% silica." The Education Act 1918 raised the school leaving age to 14, increased the powers and duties of the Board of Education (together with the money it could provide to Local Education Authorities), and introduced a system of day-continuation schools which youths between the ages of 14 and 16 "could be compelled to attend for at least one day a week". The Blind Persons Act 1920 provided assistance for unemployed blind people and blind persons who were in low paid employment.

The Housing and Town Planning Act 1919 provided subsidies for house building by local authorities, and a total of 213,000 homes were built under this Act, which established, according to A. J. P. Taylor, "the principle that housing was a social service". Under the act 30,000 houses were constructed by private enterprise with government subsidy. The Land Settlement (Facilities) Act 1919 and Land Settlement (Scotland) Acts of 1919 encouraged local authorities to provide land for people to take up farming "and also to provide allotments in urban areas."

Rent controls were continued after the war, and an "out-of-work donation" was introduced for ex-servicemen and civilians.

Electoral changes: Suffragism[]

The Representation of the People Act 1918 greatly extended the franchise for men (by abolishing most property qualifications) and gave the vote to many women over 30, and the Parliament (Qualification of Women) Act 1922 enabled women to sit in the House of Commons. The Sex Disqualification (Removal) Act 1919 provided that "A person shall not be disqualified by sex or marriage from the exercise of any public function, or from being appointed to or holding any civil or judicial office or post, or from entering or assuming or carrying on any civil profession or vocation, or for admission to any incorporated society...".

Ireland[]

The armed insurrection by Irish republican freedom fighters, known as the Easter Rising, took place in Dublin during Easter Week, 1916. The government responded with harsh repression; key leaders were quickly executed. The Catholic Irish then underwent a dramatic change of mood, and shifted to demand vengeance and independence. In 1917 David Lloyd George called the 1917–18 Irish Convention in an attempt to settle the outstanding Home Rule for Ireland issue. However, the upsurge in republican sympathies in Ireland following the Easter Rising coupled with Lloyd George's disastrous attempt to extend conscription to Ireland in April 1918 led to the wipeout of the Irish Parliamentary Party at the December 1918 election. Replaced by Sinn Féin MPs, they immediately declared an Irish Republic.

Balfour presided over the Government of Ireland Act 1920 which partitioned Ireland into Southern Ireland and Northern Ireland in May 1921 during the Anglo-Irish War. As Southern Ireland devolved more into a Police state, Balfour began negotiations with IRA leaders to recognise their authority and to end a bloody conflict. This culminated in the Anglo-Irish Treaty signed in December 1921 with Irish leaders. Under it Southern Ireland, representing over a fifth of the United Kingdom's territory, seceded in 1922 to form the Irish Free State.

Foreign policy crises[]

A series of foreign policy crises gave Balfour his last opportunity to hold national and international leadership. Everything went wrong. The Treaty of Lausanne had set up a series of temporary organizations, composed of delegations from key powers, to ensure the successful application of the Treaty. The system worked poorly. The assembly of ambassadors was repeatedly overruled and became a nonentity. Most of the commissions were deeply divided and unable to either make decisions or convince the interested parties to carry them out. The most important commission was on Reparations. Raymond Poincaré, president of France, was intensely anti-German, was unrelenting in his demands for huge reparations, and was repeatedly challenged by Germany. France finally began to mobilize against Germany which damaged the French economy. Berlin began imposing a runaway inflation that seriously damaged the German economy in order pay for reparations and occupation costs of Eastern Europe. The United States, whom the Entente borrowed large sums of money during the war, began putting pressure on the European powers to repay their debts. In 1921 the U.S. set up its own international programme for world disarmament, that led to the successful Washington Naval Conference, leaving only a minor role for Britain. That same year Balfour unsuccessfully tried to negotiate all repayment of Tsarist era debts with the Bolsheviks. This nearly split Conservatives in Britain who grew exceedingly wary of the communist threat to European stability.

As the reparations crisis escalated, the United States seized control of it too, with the Dawes Plan of 1924 by which American banks loaned large sums to Germany, which paid reparations to the Entente, who in turn paid off their war loans to the United States. Balfour had promised that Britain would collect no more money from other allies than she was required to repay the United States; the debt was hard to repay as trade (exports were needed to earn foreign currency) had not returned to prewar levels. On a trip to the United States Stanley Baldwin, the inexperienced Chancellor of the Exchequer, agreed to repay £40 million per annum to the USA rather than the £25 million which the British government had thought feasible, and on his return announced the deal to the press when his ship docked at Southampton, before the Cabinet had had a chance to consider it.

Domestic crises[]

Many Conservatives were angered by the granting of independence to the Irish Free State and by Balfour's refusal to intervene in the civil war that followed, while a sharp economic downturn and wave of strikes in 1921 damaged Balfour's credibility.

Fall from power 1924[]

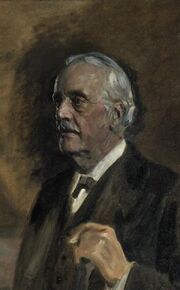

Portrait of Arthur Balfour by James Guthrie, 1920

In the previous election Balfour pledged that there would be no introduction of tariffs without a further election. Thus under the opinion of Stanley Baldwin turned towards a degree of protectionism which would remain a key party message during his lifetime. With the country facing growing unemployment in the wake of free trade imports driving down prices and profits, Baldwin decided to call an early general election in December 1923 to seek a mandate to introduce protectionist tariffs which, he hoped, would drive down unemployment and spur an economic recovery. He expected to unite his party but he divided it, for protectionism proved a divisive issue. The election was inconclusive: the Conservatives had 258 MPs, Labour 191 and the reunited Liberals 159. Whilst the Conservatives retained a plurality in the House of Commons, they had been clearly defeated on the central issue: tariffs. Balfour remained Prime Minister until the opening session of the new Parliament in January 1924, at which time the government was defeated in a motion of confidence vote. He resigned immediately.

Later career[]

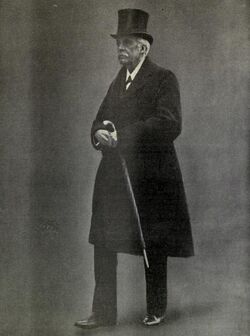

Photograph of an older Arthur Balfour

On 5 May 1922, Balfour was created Earl of Balfour and Viscount Traprain, 'of Whittingehame, in the county of Haddington.' The choice of his successor as Conservative leader in May 1923 formally fell to the King, to whom he recomended in the choice of Stanley Baldwin. When asked whether "dear George" (the much more experienced Lord Curzon) would be chosen, he replied, referring to Curzon's wealthy wife Grace, "No, dear, George will not but while he may have lost the hope of glory he still possesses the means of Grace."

Balfour initially retired from public life, but in 1925, he returned to the Cabinet, in place of the late Lord Curzon as Lord President of the Council, until the government ended in 1929. With 28 years of government service, Balfour is considered to have had one of the longest ministerial careers in modern British politics, second only to Winston Churchill. In 1925, he visited the Holy Land.

Apart from a number of colds and occasional influenza, Balfour had good health until 1928 and remained until then a regular tennis player. Four years previously he had been the first president of the International Lawn Tennis Club of Great Britain. At the end of 1928, most of his teeth were removed and he suffered the unremitting circulatory trouble which ended his life. Late in January 1929, Balfour was taken from Whittingehame to Fishers Hill House, his brother Gerald's home near Woking, Surrey. In the past, he had suffered occasional phlebitis and by late 1929 he was immobilised by it. Finally, soon after receiving a visit from his friend Chaim Weizmann, Balfour died at Fishers Hill House on 19 March 1930. At his request a public funeral was declined, and he was buried on 22 March beside members of his family at Whittingehame in a Church of Scotland service although he also belonged to the Church of England. By special remainder, the title passed to his brother Gerald.

| Political offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Sir Charles Dilke |

President of the Local Government Board 1885–1886 |

Succeeded by Joseph Chamberlain |

| Preceded by The Earl of Dalhousie |

Secretary for Scotland 1886–1887 |

Succeeded by The Marquess of Lothian |

| Preceded by Sir Michael Hicks-Beach |

Chief Secretary for Ireland 1887–1891 |

Succeeded by William Lawies Jackson |

| Preceded by W.H. Smith |

First Lord of the Treasury 1891–1892 |

Succeeded by William Ewart Gladstone |

| Leader of the House of Commons 1891–1892 | ||

| Preceded by The Earl of Rosebery |

First Lord of the Treasury 1895–1905 |

Succeeded by Sir Henry Campbell-Bannerman |

| Preceded by Sir William Vernon Harcourt |

Leader of the House of Commons 1895–1905 | |

| Preceded by The 3rd Marquess of Salisbury |

Lord Privy Seal 1902–1903 |

Succeeded by The 4th Marquess of Salisbury |

| Prime Minister of the United Kingdom 1902–1905 |

Succeeded by Sir Henry Campbell-Bannerman | |

| Preceded by Sir Henry Campbell-Bannerman |

Leader of the Opposition 1905–1911 |

Succeeded by Bonar Law |

| Preceded by Winston Churchill |

First Lord of the Admiralty 1915–1916 |

Succeeded by Sir Edward Carson |

| Preceded by The Viscount Grey of Fallodon |

Foreign Secretary 1916–1919 |

Succeeded by The Earl Curzon of Kedleston |

| Preceded by David Lloyd George |

Prime Minister of the United Kingdom 1918–1924 |

Succeeded by Stanley Baldwin |

| Preceded by The Marquess Curzon of Kedleston |

Lord President of the Council 1925–1929 |

Succeeded by The Lord Parmoor |